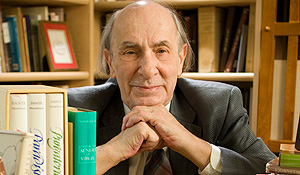

Professor Emeritus Allen Mandelbaum, a preeminent scholar of classical and Italian literature who was widely recognized as the world’s leading translator of Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” died Oct. 27 in Winston-Salem. He was 85.

Professor Emeritus Allen Mandelbaum, a preeminent scholar of classical and Italian literature who was widely recognized as the world’s leading translator of Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” died Oct. 27 in Winston-Salem. He was 85.

A graveside service for Mandelbaum was held on Oct. 30 on Long Island, N.Y. A campus memorial service is being planned for the spring.

Mandelbaum is survived by his wife Marjorie, their son Jonathan and his wife Anne, and two grandchildren, Elisa and Nicholas.

Memorial gifts may be made to the Mandelbaum Fund in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library, P.O. Box 7227, Winston-Salem, N.C., 27109. Notes of condolence may be sent to: The Mandelbaum Family, c/o Mrs. Lily Saadé, 1021 Paschal Drive, Winston-Salem, N.C., 27106.

Few, if any, faculty members in Wake Forest’s history have attained a worldwide status comparable to Mandelbaum’s. He completed his crowning achievement, a three-volume verse translation of the “Divine Comedy,” five years before joining the Wake Forest faculty in 1989 as the W.R. Kenan Professor of Humanities. Before retiring in 2008, he would also receive acclaim – on both sides of the Atlantic — for his powerful poetic translations of Homer’s “Odyssey,” Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” and other works.

Mandelbaum’s knowledge of history, literature, culture, religion, and modern and classical languages created a scholar of unusual distinction, said Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43). “He had a breadth of knowledge and experience that is remarkable in any age, but particularly remarkable now, when somehow the old patterns and commitments of learning have changed.”

James Hans, Charles E. Taylor Professor of English at Wake Forest, first met Mandelbaum in 1975 when he took a graduate class with him at Washington University in St. Louis. “He was one of a kind. Without question, he was the most learned man I’ve ever known. We won’t see any more like him.”

Jonathan Mandelbaum, who lives outside Paris, France, said his father strongly believed that it was his duty to fulfill the talents he had been given as a poet and translator. “His true calling on earth was his poetic mission.”

“He had spent his life preparing for the ultimate journey. All the masterpieces of classical and medieval literature that he translated were, in a sense, chronicles of immense journeys. That near-obsession with travel, that restlessness, that curiosity, led him to spend more time and effort translating the works of other faiths, even as he remained true to his Jewish roots.”

But his father displayed a lighter side as well, said Jonathan Mandelbaum, who followed in his father’s multilingual footsteps, but in a far different area, translating technical and scholarly texts from French and Italian into English. When he was young, his father would write poems about his goldfish or hamster. Once, when a neighbor at the Faculty Apartments where Mandelbaum lived for many years gave him some pecans, he penned an ode to that delicacy.

Mandelbaum succeeded the esteemed Germaine Brée when he came to Wake Forest. While a scholar of international renown, he especially enjoyed teaching and introducing undergraduates to the classics, Wilson and Hans said. Students loved his classes, even if they had trouble keeping up with him, because they knew they were learning from the best, Hans said.

Professor of English Gale Sigal, who studied with Mandelbaum when she was a student at the Graduate School of the City University of New York, said Mandelbaum “was a genius of a man, an inspiring mentor and teacher, and a most generous human.” In an essay in the Wake Forest Magazine in 1991, she recalled that Mandelbaum brought a world of culture, refinement and creativity to the classroom. “It was a true education, leading students to a lofty plateau from which they could feel, after the arduous climb, the thrill of learning, the satisfaction that accompanies the attainment of a new understanding.”

Mandelbaum’s oversized intellect and persona often masked a generous and caring man to those who didn’t know him well, friends said. Students and others would often tell of the impact that he had on their lives, said Lily Saadé, who was Mandelbaum’s assistant for 20 years. “He was a grand man to work with. He had a wonderful zest for life, and a remarkable creative energy, expressed in his work and in his teaching.”

Mandelbaum was especially revered in Italy, where he received a number of honors and awards, including the country’s highest award, the Presidential Cross of the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity, and the National Award for Verse Translation. In 2000, he became the first translator to receive the Gold Medal of Honor from the city of Florence for his translation of Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” given on the 735th anniversary of Dante’s birth. He taught at the University of Torino for five years and was the first American to earn the title of Professore Ordinario per Chiara Fama.

The depth and breadth of Mandelbaum’s scholarship – more than a dozen translations of classical works, half a dozen volumes of his own poetry, numerous other edited volumes – spanned five decades. His verse translations of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” (“Inferno,” “Purgatorio” and “Paradiso”), completed in 1984, are regarded as the finest ever written. He received the 1973 National Book Award for his translation of Virgil’s “Aeneid,” and was a finalist for the 1994 Pulitzer Prize in poetry for his translation of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.”

His verse translations also include Giuseppe Ungaretti’s “Life of a Man” (1958); Salvatore Quasimodo’s “Selected Writings” (1960); “The Selected Poems of Giuseppe Ungaretti (1975); “Ovid in Sicily” (1986); “Ungaretti and Palinurus” (1989); and Homer’s “Odyssey” (1990).

He was also a talented poet in his own right. His poetry collections include “Journeyman” (1967); “Leaves of Absence” (1976); “Chelmaxioms: The Maxims, Axioms, Maxioms of Chelm” (1978); “A Lied of Letterpress” (1980); “The Savantasse of Montparnasse” (1988) and “Le porte di eucalipto” (2007).

Mandelbaum donated his personal papers and much of his personal library several years ago to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library. Many of the honors and awards he received are displayed in the Mandelbaum Reading Room in the library.

A native of Albany, N.Y., Mandelbaum lived in Louisville, Ky.; Toronto; Troy, N.Y.; and Chicago, before his family settled in New York City when he was 13. He received his B.A. from Yeshiva University and a master’s and Ph.D. at Columbia. After teaching at Cornell, Columbia, Yeshiva and Hunter College, he was a Rockefeller Fellow in Humanities and a Fulbright Research Scholar in Italy.

In 1951, he was named to the Society of Fellows at Harvard and spent much of the next decade living in Italy, translating the works of Italian poets. After returning to the United States in 1964, he taught and chaired the English graduate faculty at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for 20 years. He held visiting appointments at a number of universities, including Purdue, Washington University and the University of Houston before joining the Wake Forest faculty.

— By Kerry M. King (’85), Wake Forest Magazine

Categories: Faculty News

Tags: Allen Mandelbaum, Deaths, Humanities

Recent Posts

-

April 22, 2024

-

April 22, 2024

-

April 19, 2024